What follows is a companion piece to the preceding post in that it provides yet more evidence that a very large number of Muslims, most of whom are Sunni, are doing immense harm around the world. In the process, such Muslims are denying to millions of people the basic human right to express their religion or belief in ways that no people of sound mind could object to. Inevitably, if Muslims were the victims of the discrimination and persecution they impose on others, they would be the first to say that their human rights were being infringed.

This “Religious Freedom in the World” report finds that, within the period under review (June 2014 to June 2016), religious liberty has declined in 11 – nearly half – of the 23 worst-offending countries. In seven other countries in this category, the problems were already so bad they could hardly get any worse. Our analysis also shows that, of the 38 countries with significant religious freedom violations, 55% remained stable regarding religious freedom and in only 8% – namely Bhutan, Egypt and Qatar – the situation improved.

The report confounds the popular view that governments are mostly to blame for persecution. Non-state actors (that is, fundamentalist or militant organisations) are responsible for persecution in 12 of the 23 worst-offending countries.

The period under review has seen the emergence of a new phenomenon of religiously motivated violence which can be described as Islamist hyper-extremism, a process of heightened radicalisation, unprecedented in its violent expression. Its characteristics are:

a) an extremist creed and a radical system of law and government;

b) systematic attempts to annihilate or drive out all groups who do not conform to its outlook, including co-religionists, moderates and those of different traditions;

c) cruel treatment of victims;

d) use of the latest social media, notably to recruit followers and to intimidate opponents by parading extreme violence;

e) a global impact – enabled by affiliate extremist groups and well-resourced support networks.

This new phenomenon has had a toxic impact on religious liberty around the world:

a) since mid-2014, violent Islamist attacks have taken place in one in five countries around the world – from Sweden to Australia and including 17 African nations;

b) in parts of the Middle East, including Syria and Iraq, Islamist hyper-extremism is eliminating all forms of religious diversity and is threatening to do so in parts of Africa and the Asian sub-continent. The intention is to replace pluralism with a religious monoculture;

c) Islamist extremism and hyper-extremism, observed in countries including Afghanistan, Somalia and Syria, have been a key driver in the sudden explosion of refugees which, according to United Nations figures for the year 2015, went up by 5.8 million to a new high of 65.3 million;

d) in Central Asia, hyper-extremist violence is being used by authoritarian regimes as a pretext for a disproportionate crackdown on religious minorities, curtailing civil liberties of all kinds, including religious freedom;

e) in the West, hyper-extremism is at risk of destabilising the socio-religious fabric, with countries sporadically targeted by fanatics and under pressure to receive unprecedented numbers of refugees mostly of a different faith to the indigenous communities. Manifest ripple effects include the rise of right-wing and populist groups; restrictions on free movement; discrimination and violence against minority faiths; and a decline of social cohesion, including in state schools.

There has been an upsurge of anti-Semitic attacks, notably in parts of Europe.

Mainstream Islamic groups are now beginning to counter the hyper-extremist phenomenon through public pronouncements and other initiatives through which they condemn the violence and those behind it.

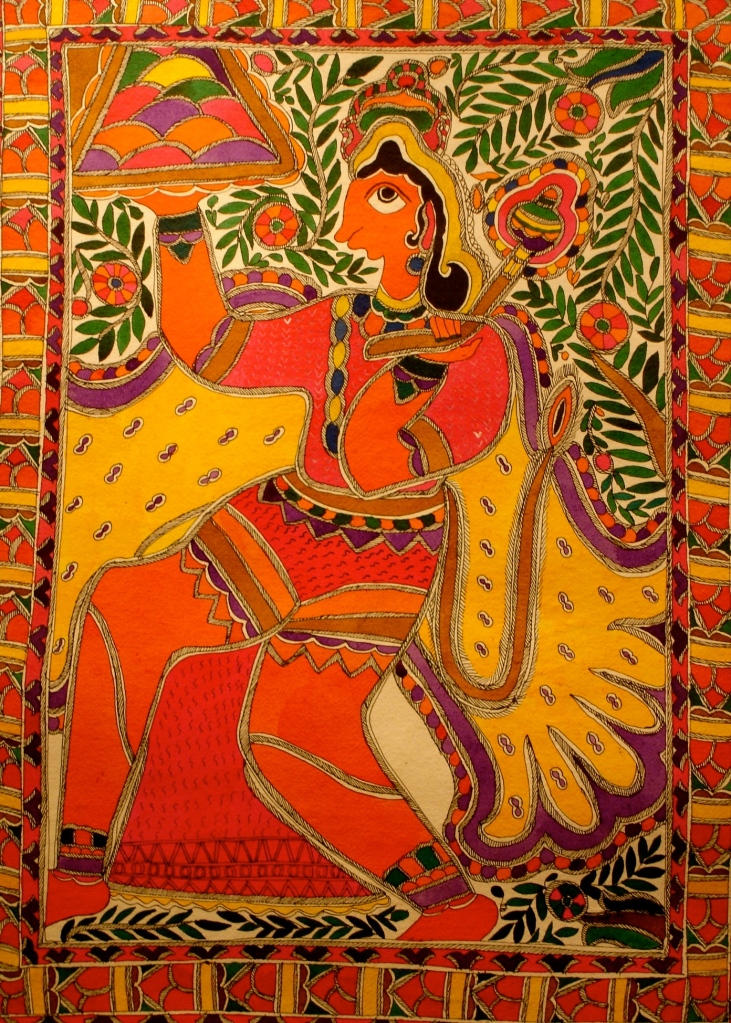

In countries such as India, Pakistan and Myanmar, where one particular religion is identified with the nation state, steps have been to taken to defend the rights of that faith as opposed to the rights of individual believers of all backgrounds. This has resulted in more stringent religious freedom restrictions on minority faith groups, increasing obstacles for conversion and the imposition of greater sanctions for blasphemy.

In the worst-offending countries, including North Korea and Eritrea, the ongoing penalty for religious expression is the complete denial of rights and liberties – such as long-term incarceration without fair trial, rape and murder.

There has been a renewed crackdown on religious groups that refuse to follow the party line under authoritarian regimes such as those in China and Turkmenistan. For example, in China, more than 2,000 churches have had their crosses demolished in Zheijang and nearby provinces.

By defining a new phenomenon of Islamist hyper-extremism, the report supports widespread claims that, in targeting Christians, Yazidis, Mandeans and other minorities, Daesh (ISIS) and other fundamentalist groups are in breach of the UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.

They showed us videos of beheadings, killings and ISIS battles. [My instructor] said, “You have to kill kuffars [unbelievers] even if they are your fathers and brothers, because they belong to the wrong religion and they don’t worship God.”

The above is an excerpt from a Yazidi boy’s account of what happened to him when he was captured by Daesh aged 12 and trained for jihad in Syria. It is one of 45 interviews with survivors, religious leaders, journalists and others describing atrocities committed by Daesh which form the basis of a landmark report issued in June 2016 by the United Nations Human Rights Council. Citing evidence to show that an ongoing genocide has been taking place against Yazidis, the 40-page report makes clear that Daesh has sought to “destroy” Yazidis since 2014 and that religious hatred was a core motivation. This point is underlined in a case study which tells the story of teenage Yazidi girl Ekhlas, who describes how the militants killed her father and brother for their faith. She herself watched helplessly as Yazidi women were repeatedly raped, including a girl of nine who was so badly sexually abused that she died.

Ekhlas’s experience, and that of so many others like her, demonstrates the importance of religious freedom as a core human right. Increasing media coverage of violence perpetrated in the name of religion – be it by Boko Haram in Nigeria, Al-Shabaab in Kenya or the Taliban in Afghanistan – reflects a growing recognition about how for too long religious liberty has been “an orphaned right”. Aided by the work of political activists and NGOs, a tipping point has been reached concerning public awareness about religiously motivated crimes and oppression, prompting a fresh debate about the place of religion in society. The frequency and intensity of atrocities against Yazidis, Christians, Bahais, Jews and Ahmaddiyya Muslims is on the rise, and is reflected in the volume of reporting on extremist violence against religious minorities.

In the face of such crimes, it is arguably more important than ever to arrive at a clear and workable definition of religious freedom and its ramifications for government and the judiciary. This report acknowledges the core tenets of religious liberty as contained in Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted by the United Nations in 1948:

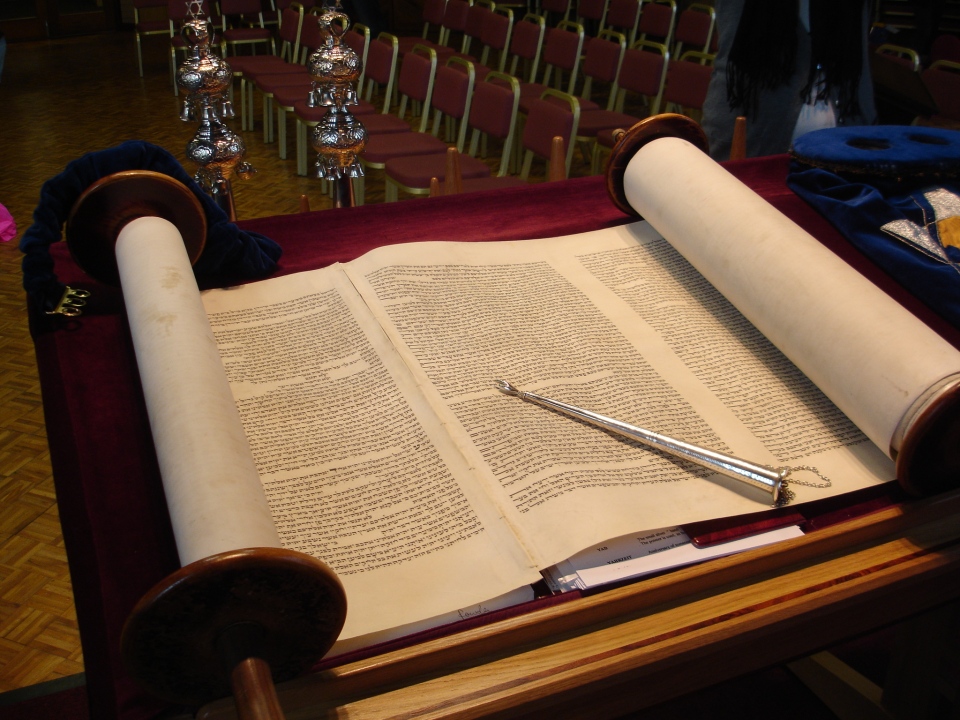

Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief; and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship or observance.

The focus of this report is concerned with state and non-state actors (militant or fundamentalist organisations) who restrict and deny religious expression, be it in public or in private, and who do so without due respect for others or for the rule of law.

Examining the two-year period up to June 2016, this report assesses the religious situation of every country in the world. In total, 196 nations were examined with a special focus in each case on the place of religious freedom in constitutional and other statutory documents, incidents of note and finally a projection of likely trends. Consideration was given to recognised religious groups regardless of their numerical size or perceived influence in any given country. Each report was then evaluated, with a view to creating a table of countries where there are significant violations of religious freedom. In contrast to the 2014 “Religious Freedom in the World” report which categorised every country in the world, the table on pages 32-35 and the corresponding map on pages 30-31 focus on 38 countries where violations against religious freedom go beyond comparatively mild forms of intolerance to represent a fundamental breach of human rights.

The countries where these grave violations occur have been placed into two categories – “Discrimination” and “Persecution” (for a full definition of both categories, visit http://www.religion-freedom-report.org). In these cases of discrimination and persecution, the victims typically have little or no recourse to law.

In essence, “discrimination” ordinarily involves an institutionalisation of intolerance, normally carried out by the state or its representatives at different levels, with legal and other regulations entrenching mistreatment of individual groups, including faith-based communities. Examples would include no access to – or severe restrictions regarding – jobs, elected office, funding, the media, education or religious instruction, prohibition of worship outside churches, mosques, etc., and restrictions on missionary endeavour including anti-conversion legislation.

Whereas the “discrimination” category usually identifies the state as the oppressor, the “persecution” alternative also includes terrorist groups and non-state actors, as the focus here is on active campaigns of violence and subjugation, including murder, false detention and forced exile, as well as damage to and expropriation of property. Indeed, the state itself can often be a victim, as seen, for example, in Nigeria. From this definition, it is clear that “persecution” is a worse-offending category, as the religious freedom violations in question are more serious, and by their nature also tend to include forms of discrimination as a by-product. Of course, many, if not most, of the countries not categorised as falling under “persecution” or “discrimination” are subject to forms of religious freedom violations. Indeed, many of them can be described as countries in which one or more religious groups experience intolerance. However, based on the evidence provided in the country reports reviewed, nearly all of these violations were still illegal according to the authorities, with the victim having recourse to law. None of these violations – many of them by definition low level – was considered serious enough to warrant description as significant or extreme, the two watchwords in our system of categorisation. On this basis, for the purposes of this report they are listed as “unclassified”.

Of the 196 countries reported on, 38 showed unmistakable evidence of significant religious freedom violations. Within this group, 23 were placed in the top level “persecution” category, and the remaining 15 in the “discrimination” category. Since the last report was released two years ago, the situation regarding religious freedom had clearly worsened in the case of 14 countries (37%), with 21 (55%) showing no signs of obvious change. Only in three countries (8%) had the situation clearly improved – Bhutan, Egypt and Qatar. Of the “persecution” countries, 11 – just under half – were assessed as places where access to religious freedom was in marked decline. Among the “persecution” countries showing no discernible signs of improvement, seven were characterised by extreme scenarios (Afghanistan, Iraq, [northern] Nigeria, North Korea, Saudi Arabia, Somalia and Syria) where the situation was already so bad it could scarcely get any worse. This means there is a growing gulf between an expanding group of countries with extreme levels of religious freedom abuse and those where the problems are less flagrant, for example, Algeria, Azerbaijan and Vietnam.

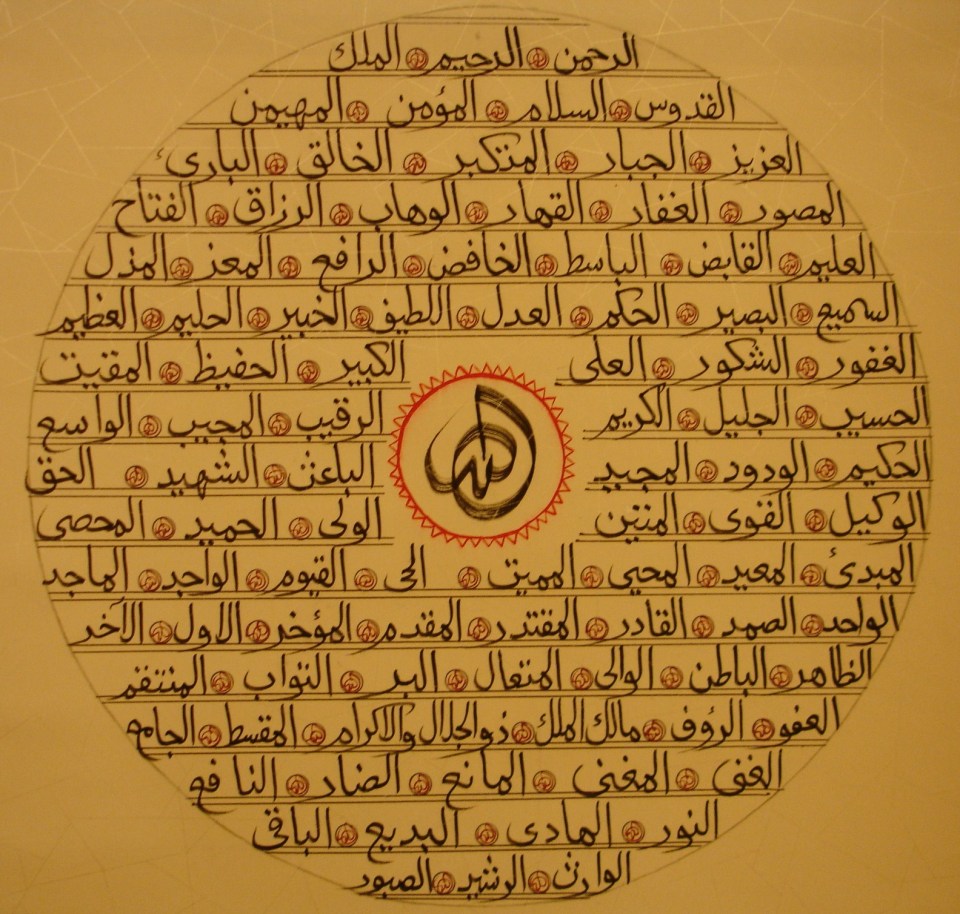

A virulent and extremist form of Islam emerged as the number one threat to religious freedom and was revealed as the primary cause of “persecution” in many of the worst cases. Of the 11 countries shown to have worsening persecution, nine were under extreme pressure from Islamist violence (Bangladesh, Indonesia, Kenya, Libya, Niger, Pakistan, Sudan, Tanzania and Yemen). Of the 11 countries with consistent levels of persecution, seven faced huge problems relating to Islamism – both non-state actor aggression and state-sponsored oppression (Afghanistan, Iraq, Nigeria, the Palestinian Territories, Saudi Arabia, Somalia and Syria).

Assessing underlying themes relating to this, it emerged that a massive upsurge in violence and instability linked to Islamism had played a significant role in creating an explosion in the number of refugees. A core finding of the report is the global threat posed by religious hyper-extremism, which to Western eyes appears to be a death cult with a genocidal intent. This new phenomenon of hyper-extremism is characterised by the radical methods by which it seeks its objectives, which go beyond suicide bomb attacks – namely, mass killing including horrific forms of execution, rape, extreme torture such as burning people alive, crucifixions and throwing people off tall buildings. One hallmark of hyper-extremism is the evident glorying in the brutality inflicted on its victims, which is paraded on social media.

As witnessed by the evidence of Yazidis reported above, the violence perpetrated by militant groups such as Daesh was indicative of a complete denial of religious freedom. The atrocities committed by these aggressive Islamist groups in Syria, Iraq and Libya, and by their affiliates elsewhere, have arguably been one of the greatest setbacks for religious freedom since the second world war. What has properly been described as genocide, according to a UN convention which uses the term, is a phenomenon of religious extremism almost beyond compare. The aggressive acts in question include widespread killings, mental and physical torture, detention, enslavement and in some extreme cases “the imposition of measures to prevent children from being born”. In addition, there has been land grabbing, destruction of religious buildings and all traces of religious and cultural heritage, and the subjection of people under a system which insults almost every tenet of human rights.

A core finding of the report, the threat of militant Islam, could be felt in a significant proportion of the 196 countries reviewed: a little over 20% of countries – at least one in five – experienced one or more incidents of violent activity, inspired by extremist Islamic ideology, including at least five countries in Western Europe and 17 African nations.

One key objective of Islamist hyper-extremism is to trigger the complete elimination of religious communities from their ancient homelands, a process of induced mass exodus. As a result of the migration, this phenomenon of hyper-extremism has been a main driver in the fundamental de-stabilisation of the socio-religious fabric of entire continents, absorbing – or under pressure to absorb – millions of people.

According to UN figures, there were an estimated 65.3 million refugees by the end of 2015 – which is the highest figure on record, and a rise of more than 9% compared to the previous year. At the time of writing, the most recent figures equate to, on average, 24 people being displaced from their homes every minute of every day during 2015. Although economic factors played a major part, the countries which largely accounted for the increase in refugees were centres of religious extremism – Syria, Afghanistan and Somalia. There were many people who were fleeing specifically because of religious persecution, but for the most part, people fled because of the violence, breakdown of government and acute poverty of which religious extremism has been cause, symptom or consequence. To this extent, extremism has been a key factor in the migrant explosion. Religious extremism has played a dominant role in the creation of terror states which are being emptied of people.

Evidence reveals that in the Middle East and parts of Africa and the Asian sub-continent, people of all faiths were leaving, but disproportionate levels of migration among Christians, Yazidis and other minority groups were raising the possibility – or even probability – of their extinction from within a region.

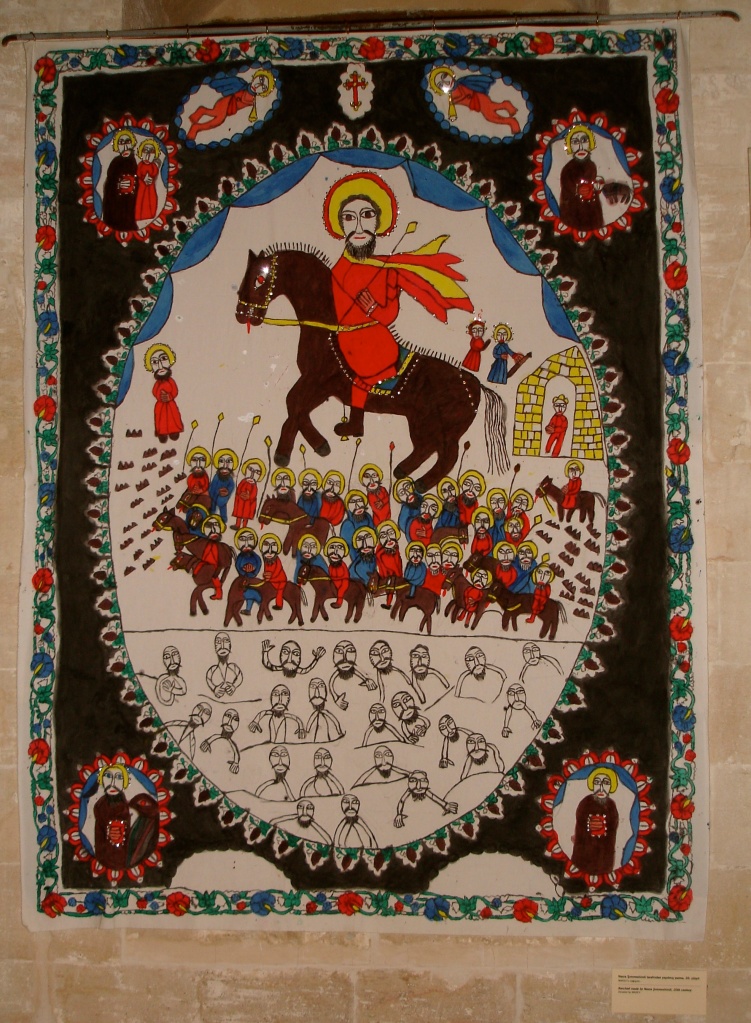

Few, if any, religious groups were neither victims nor perpetrators of persecution. This report found that among Jewish, Buddhist and Hindu communities, a growing threat came from non-mainstream but vocal groups, many of them linking faith with patriotism to create a form of religious nationalism that looks on minorities as outcasts. In Myanmar, reports emerged that on 1st July 2014, 40 Buddhist monks and 450 lay people massed on the streets in Chan Aye Thar brandishing knives and sticks and laid siege to a Muslim tea shop. In Israel, at a time of numerous religiously motivated attacks, the state’s Roman Catholic bishops made a formal complaint in December 2015 about Rabbi Benzi Gopstein. Gopstein made a statement on an ultra-Orthodox website stating, “Christmas has no place in the Holy Land” and calling for the destruction of all churches in Israel. He added, “Let us remove the vampires before they once again drink our blood.” In India, “the world’s largest democracy”, respect for minority rights has come under increasing threat from extremist Hindu groups. “Pro-Hinduisation” organisations are a source of major concern because they create a climate which leads Hindu extremists to physically attack religious minorities with relative impunity. Such a threat was demonstrated in September 2015 when Hindu extremists were reported to have brutally murdered Akhlaq Ahmed, a Muslim man who was accused of marking Eid by killing a cow and eating beef.

As can be seen, tumultuous world events during the period under review have had a deep and far-reaching impact regarding religious freedom in many countries around the world. Forces of change were dominated by the rise of Islamist hyper-extremism which has destroyed religious freedom in parts of the Middle East and is threatening to do the same in other parts of the world. Increased awareness about the threat to religious minorities has been reflected in the actions of politicians, parties and even some parliaments who are doing more than ever before to speak up and act on behalf of persecuted individuals and communities. One ray of hope is the willingness of some Islamic leaders to mount a coordinated response to this toxic creed. Activities of the security services will never be able to challenge the ideology behind this threat. Only religious leaders themselves can take on that challenge. One over-riding conclusion is the need to find new and coordinated ways so that religious plurality can return to those parts of the world where minority groups are being “threatened in their very existence”.

The list of “persecution” states:

Afghanistan, Bangladesh, China, Eritrea, India, Indonesia, Iraq, Kenya, Libya, Myanmar, Niger, Nigeria, North Korea, the Palestinian Territories, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tanzania, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Yemen.

The list of “discrimination” states:

Algeria, Azerbaijan, Bhutan, Brunei, Egypt, Iran, Kazakhstan, Laos, Maldives, Mauritania, Qatar, Tajikistan, Turkey, Ukraine, Vietnam.

Where religious freedom has worsened over the last two years:

Bangladesh, Brunei, China, Eritrea, Indonesia, Kenya, Libya, Mauritania, Niger, Pakistan, Sudan, Tajikistan, Tanzania, Yemen.

I agree with a lot of the conclusions contained in the sections of the report quoted above, including the conclusion that Muslims in many parts of the world aspire to create monocultural environments in which followers of non-Muslim expressions of religion and belief no longer exist (for many Sunni Muslims, they additionally aspire to create environments in which only Sunni Islam exists. In other words, Shia, Sufi, Alevi and Ahmadiyya Muslims are as unwelcome as people subscribing to religions such as Christianity, Judaism or Yazidism). I also find quite helpful the concept of hyper-extremism as a way of identifying manifestations of religious extremism that lead to the active persecution of groups identified as the despised other.

What we can say with confidence is that, today, extremism manifests itself in almost every expression of religion, mainstream or otherwise, but, thankfully, not all religious extremists engage in the sort of persecution alluded to in the report, persecution that includes the destruction of homes and religious buildings, torture, rape, expulsion, massacre and/or genocide. Most religious extremists confine their hatred to rhetoric alone. Such hatred is bad enough, but it is when such hatred morphs into action that we need to worry the most.

It is right that most attention is given in the report to the dire consequences of what it calls Islamist hyper-extremism, but one concern I have is that it largely overlooks that hyper-extremism exists in other expressions of religion, albeit involving far fewer people and thus having detrimental consequences that are not so great. I would argue that some Buddhists in Myanmar, some Christians in the United States, some Hindus in India, some Jews in Israel and some Sikhs in Punjab manifest hyper-extremism which occasionally leads to persecution of the despised other comparable to that which derives from Muslim hyper-extremists. But don’t misunderstand me. Buddhist, Christian, Hindu, Jewish and Sikh hyper-extremists do not pose anything like the same threat that Muslim hyper-extremists do, and I very much doubt that they ever will. But exist they do and the report could have done more to expose what I regard as a worrying trend in all the world’s major expressions of religious belief.

Of course, the other thing the report might have discussed productively is what sustains such extremism. It has long been my contention that religious extremism is above all predicated on one or more of the following: literal interpretations of scripture long past its best-by date; misleading information about religious authority figures, especially ones dead for so long that very little can be said about them with any degree of certainty; and the self-evidently daft idea that any religion might be the only source of truth, wisdom, knowledge and/or understanding. All religions are human inventions and most religions discourage critical analysis and informed debate based on hard evidence. It is because of these realities that most expressions of religion find themselves susceptible to manipulation by extremists. How refreshing it would therefore have been had the report admitted that extremism exists in the Roman Catholic Church and that, as a consequence, the Church must engage in reform to make it less likely for it to prosper.

These points apart, the report has much to commend it, which is why I quote from it so extensively.