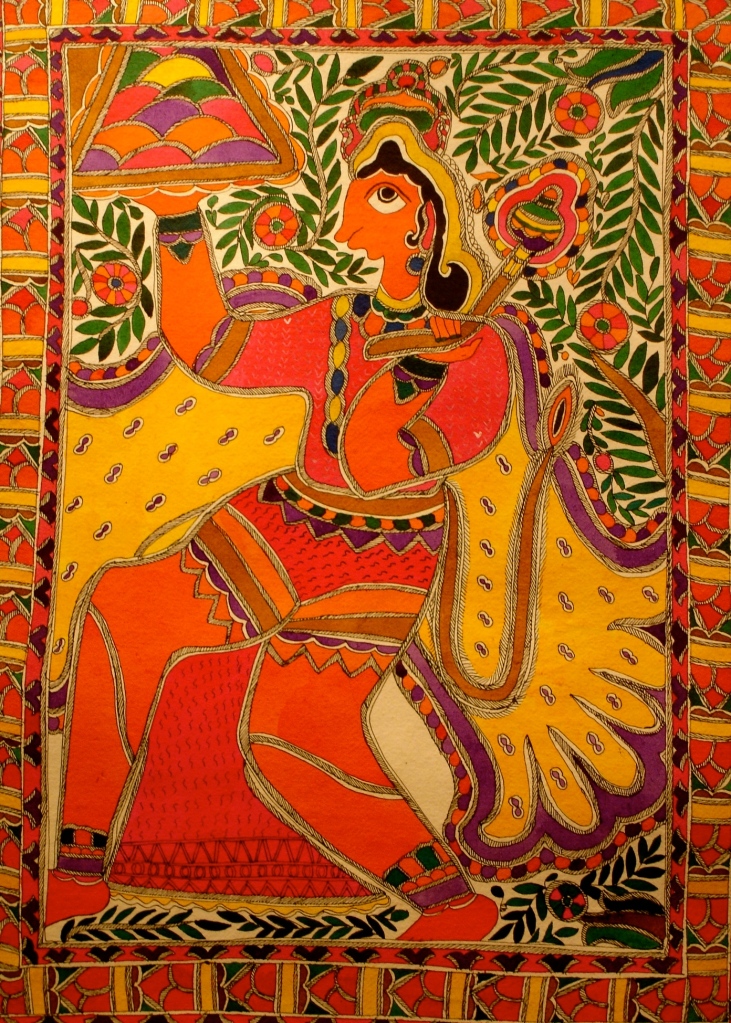

Shiva and Parvati, manifestations of the divine in male and female forms. Gender equality in Hinduism?

Why is it that most expressions of religion deny girls and women the same opportunities as boys and men? Is it that God, gods, the supreme being/beings, ultimate reality and/or the divine are all too often described as if they are male? Is it that men and not women wrote all or most of the world’s scripture? Is it that men edited scripture in such a way that women’s contributions were distorted/suppressed? Is it predicated on the daft idea that the physically powerful (males) should always shape life for the physically less powerful (females)? Is it predicated on the equally daft idea that males are intellectually superior to females?

Goddesses and women have played diverse but significant roles in many religions, so why have they been nearly invisible in the official stories of most of them? In the contemporary world, women often make up the majority in congregations or gatherings for religious purposes, but they are less well represented in leadership positions.

I am not convinced that religions are necessarily sexist in their beliefs, practices, predispositions or general character. By way of opening up discussion about this matter of supreme and fundamental importance about religious commitment (a religion that cannot treat males and females as equals is highly suspect and deserves condemnation to encourage it to immediately mend its ways), I will dwell on the case of Christianity, which, in its very earliest decades, looked as if it would present a formidable challenge to prevailing norms about gender roles. It is therefore very depressing that males of sometimes questionable character (e.g. note the disquiet expressed about the abuse of children, some of it of a sexual nature, in the first three or four centuries of Christianity’s existence. Have things changed that much since?) seized the reins of authority and quickly marginalised women. In other than only a few fleeting instances thereafter, it was not until two centuries following the Reformation in the 16th century that some of the Protestant churches began to address the issue of gender equality in a serious and holistic manner (although some expressions of Christianity prior to the Reformation allowed women to attain positions of considerable influence, but only within monastic orders).

A general comment to begin with. To a very large degree, the Bible was written by men for men about men (this is also the case in relation to scripture in many other religious traditions). However, in John’s Gospel, women are active, innovative and ministers of the kingdom to come. They are affirmed in roles unusual/unacceptable in contemporary Middle Eastern society.

Books of the Bible written before John’s Gospel make it clear that a woman should be the bearer of her husband’s children and satisfy her husband’s sexual appetites. Such books say that women and men are shaped by biology and biology determines their roles in society. In a lot of early Jewish literature, women are defined as unclean and sexual temptresses, and contact with women should therefore be avoided. Because they were “responsible” for male temptation and/or deviation from ethically admirable conduct, women were barred from public life lest they cause men to sin. Because women were not thought to have the intelligence of men, they were discouraged from using their initiative. In fact, it was sinful for women to study the Torah. Moreover, because they lacked intellectual ability, they could not act as witnesses.

In John’s Gospel, Jesus calls women to public ministry despite male opposition to the idea. He engages in theological discussion and debate (“I am the messiah”) with a Samaritan woman (who is doubly suspect, for being a woman and a marginalised/distrusted Samaritan). He talks with Martha about resurrection. The news of his resurrection reaches the disciples via Mary Magdalene.

Jesus is happy to interact with a marginalised Samaritan who is also a woman, someone whom many Jewish people at the time would have regarded as unclean. But it is the unclean Samaritan woman who is persuaded that Jesus is the messiah – and she abandons everything to share her knowledge with others. She is therefore a model for apostolic activity and would therefore seem to be on an equal footing with the disciples. Her role in John’s Gospel is described in the same way that John’s Gospel describes the disciples’ ministry.

The Samaritan woman is the first person in John’s Gospel to whom Jesus reveals himself as the messiah and is the first person who acts on the information. She is therefore the recipient of important theological knowledge. Jesus treats her seriously and responds to her comments patiently and thoughtfully. To a very real degree, she is a model of female discipleship. This seems to imply that women can be messengers of the kingdom.

In John’s Gospel, Martha of Bethany is introduced in such a way as to suggest that she is more important than Lazarus. Jesus delivers “I am” speeches to Martha, and Martha’s response to them mirrors that of Simon Peter in Matthew’s Gospel. Simon Peter’s response is generally viewed as confirmation that he has a leadership role, which would therefore imply that Martha is like a leader within the Jesus sect. Jesus sees Martha as capable of perceptive and discerning faith.

Even in stained glass windows, men invariably outnumber women. St. Vitus’s Cathedral, Prague, Czech Republic

If Chapter 20 of John’s Gospel is taken at face value, it would seem to provide the ultimate confirmation that Jesus is the resurrected Christ, the Son of God. Mary Magdalene finds the tomb empty and tells Peter and the Beloved Disciple. Mary Magdalene is told to tell Jesus’s brothers the news of the resurrection. She is therefore entrusted with the supremely important message of Jesus’s triumph over death. It is due to this role that Mary Magdalene has been called the apostle of the apostles. A woman is informing the male disciples about the most basic tenet of the Christian faith, about the most startling mystery at the heart of the religion. One is therefore compelled to ask, “Is Mary Magdalene the equal to Peter?”

In some key respects, therefore, Jesus in John’s Gospel is revealed as distinctly radical or even revolutionary in relation to the cultural norms of his age. He seems to confirm that women do not seduce men and that they should have access to public life. He seems to say that women should benefit from education. However, the Bible very soon confirms that all the disciples are male. Does this therefore reveal that Jesus is really a man of his time despite the above? Or does this merely suggest that others who came after him subverted his original intentions?

There is an indication in Chapter 12 verse 2 of John’s Gospel that Martha may have served at a table, perhaps as what became known as a deacon or minister in a house-church.

Although the earliest Christian texts attest to the importance of women in Jesus’s entourage and in the running of the first Christian house-church meetings, women rapidly disappear from the official history of church leadership (is this because church leaders conformed with Paul’s hostility to women playing an active public role in society and/or the church comparable to that of men?). However, sufficient historical and biblical evidence exists to confirm that in the early days of innovation Christianity accorded to women a role in the emerging religion that was indistinguishable from that of men. Consequently, far from the Church of England’s recent ordination of a woman as a bishop being a departure from early Christian tradition (for a few years already, women have been bishops in the Episcopalian Church, the version of the Church of England that exists in the USA), Anglicans have simply brought practice within their denomination into line with the seeds sown in the decades immediately following the execution of Jesus.

Torah scrolls, Reform Synagogue, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, United Kingdom. For a number of years now, the synagogue has had a female rabbi

Although the great majority of religions worldwide discriminate against women or withhold opportunities to women that they grant to men (can anyone come up with examples of sexism that are more blatant?), the Church of England, the Episcopalian Church, the Methodist Church and the United Reformed Church are among the Christian denominations that have female priests/ministers, and within Judaism, all “schools” except Orthodox ones encourage women to train as rabbis. Men and women share priestly responsibilities in ISKCON and in many manifestations of what is collectively called Paganism. Women also play a key role in rituals associated with the religion known variously as Vodou, Voodoo or Vodun (e.g. female Vodou priests are called “mambos”). In some manifestations of Sufism, men and women assume an equal role in ritual practices, and monasticism for males and females exists in many forms of Christianity and some forms of Buddhism.

Can anyone identify the other religions which accord women exactly the same opportunities as men so that they play a full/leading role within their faith? I’m not interested in the religions which allege that women are equal to men (many religions allege this, but practices soon reveal they are lying); instead, I seek evidence that this is so in terms of their authority within the religion. Put another way, if authority figures within a faith are men, can women fulfil exactly the same roles? If not, why not? If they can’t fulfil such roles, don’t tell me it’s tradition because, if it is, tradition needs to be immediately challenged. Slavery was traditional, but it no longer exists in most parts of the world (it is most common in India, however, where an estimated 14 million people – yes, 14 million people – suffer from different types of bondage or false imprisonment. Most such people are children and women). Female infanticide was traditional, but it is rarely encountered today (it appears to be most common in the People’s Republic of China). The burning of witches was traditional, but it is largely confined to only a few places in Africa and Melanesia. Human sacrifice was traditional, but it would appear to have died out everywhere (except in Louisiana, if “True Detective” is to be believed).